Words express emotions, actions and sensations. Both short Hemingway-ish power sentences and long clause-embedded beauties force me to marvel at the craft, inventive structure and grammatical placement. I go back, reread and savor an author’s phrase word by word. Reading is good food for the brain.

Words express emotions, actions and sensations. Both short Hemingway-ish power sentences and long clause-embedded beauties force me to marvel at the craft, inventive structure and grammatical placement. I go back, reread and savor an author’s phrase word by word. Reading is good food for the brain.

Now science proves what literature already knew. Neuroscience News reveals a study about predicting the areas of the brain activated by words in a sentence. Previous studies mapped the brain on the meanings associated with words. For example, the article cites the word “play” which triggers brain areas associated with biomotion and arousal. With a deliberate thought to brain play, it’s time now to hunt for some examples of brain tingling responses.

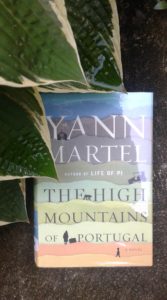

A perfect source of material is Yann Martel’s The High Mountains of Portugal. For readers of Life of Pi, Martel’s latest book combines unusual characters with somber themes, apes, and a special something extra of magical realism on the top. I listened to the audio book first and then sought the written copy to reread my favorite parts. Heck, I pretty much reread the whole book. The pure escape of Martel’s writing saved me when I had an unpleasant chore to tackle. Plugging my brain into Martel’s Portugal transformed the experience.

Lingering Despair

The novel begins with a quirky character Tomas who is heartbroken from the death of his son and the woman he loved. “ . . . he is ambushed by a memory of Dora, smiling and reaching out to touch him. For that, the cane is useful, because memories of her always throw him off balance” (Martel 2).

Martel uses the uncle to ask, “Why? Why are you doing this? Why don’t you walk like a normal person?” (9) My brain sympathizes with Tomas’ sadness and his peculiar manner of walking. Martel explains that “what his uncle does not understand is that in walking backward, his back to the world, his back to God, he is not grieving. He is objecting. Because when everything cherished by you in life has been taken away, what else is there to do but object?” (12).

Pestering Itch

Tomas begins his own quest for a sacred artifact in the high mountains. Preserving the past, the legends, and the myths, the mountains are also primitive and resist the modern. Soon, Tomas “is itchy all over, in a manner that is absolutely maddening, precisely because he is a tornado of vermin, with a civilization of lice, fleas, and whatnot dancing upon his head” (Martel 82). And ten pages later, my own skin crawls with imaginary lice. I feel Tomas’ relief when “he raises his ten fingers in the air. His blackened fingernails gleam. With a warlike cry, he throws himself into the fray. He rakes his fingernails over his head-the top, the sides, the nape–and over his bearded cheeks and neck.” And the scratching and grunting satisfaction continued for several pages, but I turn down the volume and glance around to see if any of the neighbors have come to find the source of such groans.

Nauseating Unease

Autopsy is common on the prime time television series. Martel cleverly calls “every dead body . . . a book with a story to tell, each organ a chapter, the chapters united by a common narrative” (137). My lessons in anatomy are limited to life drawing classes. Dissections ended in ninth grade biology with a starfish and frog. And my experiences with decay are limited to the latest zombie movie or the refrigerator crisper drawer. Martel lures squeamish readers, like me, into the examiner’s office. The coroner, Eusebio, “is used to being greeted by the Mortis sisters when he comes to work. The oldest, Algor, chills the patient to the ambient temperature; Livor, the middle sister, neatly applies her favourite colour scheme–yellowish grey to the top half of the patient and purple-red to the bottom half, where the blood has settled–and rigor, the youngest, so stiffens the body that bones can be broken if limbs are forced. They are cheery ones, these sisters, eternal spinsters who ravish innumerable bodies” (Martel 190). From here, the author dives deep into the stages of decay in the days after death. He pushes the descriptions to the limit; I can’t take any more. My brain on full revolt warns to avert my eyes and cover my ears. It was almost too much. It was too much. But then, before I look away, something unexpected happens. Something magical. Something beautiful. Something unreal. I want to believe. However, I also wanted to believe the notion of Pi training a tiger on a rescue boat in the middle of the ocean.

The High Mountains of Portugal is a successful storytelling rich for study. Other areas of study might include theme, structure, and magical realism. In every post, I highlight an author’s unique writing with a specific goal to avoid spoiling the reader’s full enjoyment of the plot and the story.