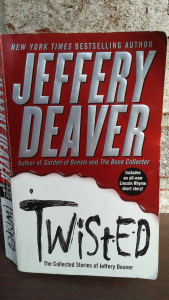

Expectations hinge on a hint of plot—a clever title, an eye-catching cover design or the hook of a story’s first sentence. I recently found three Little Free Libraries (LFL) with clear messages to prospective readers. Although my LFL discovery from last month, Twisted by Jeffery Deaver, makes me suspicious of every motive and surprise plot twist, Deaver delivers suspense from the beginning to the end. Today, however, everything is exactly as it appears.

Expectations hinge on a hint of plot—a clever title, an eye-catching cover design or the hook of a story’s first sentence. I recently found three Little Free Libraries (LFL) with clear messages to prospective readers. Although my LFL discovery from last month, Twisted by Jeffery Deaver, makes me suspicious of every motive and surprise plot twist, Deaver delivers suspense from the beginning to the end. Today, however, everything is exactly as it appears.

Little Free Library #1 – Young and Wild

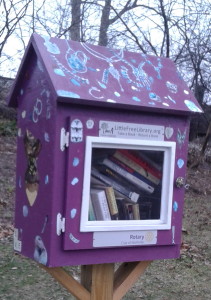

After a brisk walk, I find LFL #1 in a small green space. In the spirit of modern art, this LFL’s exterior captures the human experience of bold strikes against nature. Artwork like this requires considerable skill to accomplish the appearance of such complete randomness. The book collection tumbles from the shelves. The library’s selection aims for a younger audience.

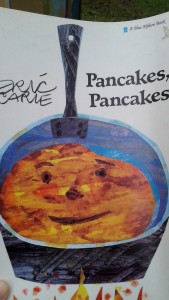

What’s this? Eric Carle? Pancakes? I’ve never read this book. I flip through the pages. It’s Carle collage magic. I want to read it, enjoy the hand-painted paper and deceptively clever plot. Should I take it? Instead of depriving a child of Carle’s artwork, I put the book back and find Czech Cookery. I love quirky cookbooks. I search the index for Kolaches. I’m converting to gluten free when I feel a tap on my shoulder. Did I mention I recruited my spouse to come along? He asks if I really want to find all the LFLs in less than one hour. I put the cookbook back, and we walk south for the long stretch to LFL #2.

I’ve never read this book. I flip through the pages. It’s Carle collage magic. I want to read it, enjoy the hand-painted paper and deceptively clever plot. Should I take it? Instead of depriving a child of Carle’s artwork, I put the book back and find Czech Cookery. I love quirky cookbooks. I search the index for Kolaches. I’m converting to gluten free when I feel a tap on my shoulder. Did I mention I recruited my spouse to come along? He asks if I really want to find all the LFLs in less than one hour. I put the cookbook back, and we walk south for the long stretch to LFL #2.

The spouse is much better with time management, but he’s a magnet for ladies asking for directions. And as with most of our walks, a car with somebody’s mother pulls along side us when I’m in my aerobic pathway. Directions to Detroit? That will take at least ten minutes to explain. No, no, don’t pull out the phone. Not the GPS. I’m jogging in place when he gives me the “chill out” look that both my sons’ inherited. I fidget through his five minutes of instructions and inform him that we will have to walk faster and maybe have to cut through the horse carriage racing track, dodge horse trailers and off-track gamblers rushing to place the big bet of the day. The spouse holds a hand skyward. I feel it too—the occasional drop of rain.

Little Free Library #2 – Whimsical, Worldly and Wise

Little Free Library #2 – Whimsical, Worldly and Wise

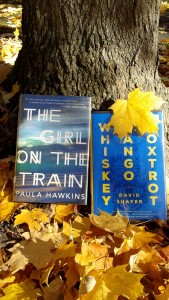

This LFL is in a parking lot beside the Chamber of Commerce and next to rarely traveled railroad tracks. Despite the setting, the box exudes a magical aura like the tickling of glass or the floating of a hovering hummingbird drawn to a flower. I’m attracted to this box and take a moment to organize the contents. I line up my final two choices of literary fiction, Graham Greene and Richard Brautigan. “Revenge of the Lawn” gets my vote. I tuck the paperback in my jacket to protect it from the rain.

We walk west again and curve northward past the historical gristmill turned fitness club. I am a few steps toward the historical village, when I discover a Starbuck’s tractor beam latched on to the spouse luring him in the opposite direction. He says we don’t have time for the last box. It’s raining. He suggests we get a coffee instead. It’s a quest. We must go.

Little Free Library #3 – Meticulous and Meaningful

The last LFL is a tribute to Americana, little red schoolhouses, and all things learned and studious. The library is in a small park in a neighborhood nicknamed “cabbage patch” with playground equipment and benches. You can’t see it in the photo, but a steady rain falls on the fire-engine red sides with precision painted shingles and picket fence. This LFL replicates everything fiery about reading and learning. I find inside my fire, Flash Boys, by Michael Lewis, the book written by the same author as The Big Short. I take it. The spouse sighs and ambles to the new brew pub near Main.

My quest highlights the collaborative result of the Rotary Club, the Art House and the Public Library to place kitschy Little Free Libraries in the public and encourage reading. I have a bag of books sorted to go to each library for the appropriate audience. If you have a Little Free Library in your life, please feel free to share the art and contents of your box.

My quest highlights the collaborative result of the Rotary Club, the Art House and the Public Library to place kitschy Little Free Libraries in the public and encourage reading. I have a bag of books sorted to go to each library for the appropriate audience. If you have a Little Free Library in your life, please feel free to share the art and contents of your box.