What did happen to Abram’s money? He never made it to Switzerland so he couldn’t have taken the money out or sent it to America. I used to wonder, when I was a child, and my Mom entertained us each night before bed by telling us stories about her two trips to Europe and how hard it was trying to bring Abram to America, what happened to the money?

As I got older I understood that, in those days, once you put money in a Swiss bank account, you only needed to know the account number to take your money out. No account ever had a name attached to it. People put their money in Switzerland’s banks because their laws allowed depositors to keep their accounts secret and anonymous.

Then I remembered Maximillian, Abram’s younger brother. He had come to America twice with Abram, in 1919 and 1929. From Mom’s stories the two seemed to always be together. According to the letters I read, they were both together in Beirut, Lebanon in the early part of 1941. Abram was thinking about money at that time because he wrote to my grandparents that he was almost without funds and so he couldn’t stay much longer.

Did Abram give Maximillian the account numbers then? Just in case something bad should happen to him?

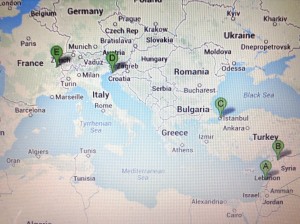

I talked to my Mom, who’s 101, and asked her why Maximillian didn’t go with Abram when he started out for Switzerland? It seemed strange that the two of them would separate at that point. She didn’t know. But the two did separate with Abram traveling to Switzerland and Maximillian going to Romania.

She remembered that at some point, when Maximillian was in Romania, he was captured by the Nazis and put in a German concentration camp. She didn’t know which one. He escaped once. But then he was caught and imprisoned again. At the end of World War II the Russians liberated the concentration camp. He was out for a while. Then the Russians arrested him and put him in one of their camps. Some time later, he tried to escape and this time he was successful.

Maximillian contacted the Red Cross. They were able to connect him with my grandparents. He told them that he was out, but he needed money desperately. I remember that for years my parents and grandparents talking about what they were sending to Maximillian to sell. At one point he wanted material to make men’s suits so he could sew and sell them. My grandparents wanted to send him ready-made suits. It would have been easier for them. But, no, he insisted they send him the material instead. Why? We never found out.

Another time, they thought he could make more money, and it would be cheaper for them to mail, if they sent him watches. He was very angry. Apparently, the Russians or the Germans, I’m not clear which, beat him. They thought the watches contained some type of device to make a bomb.

Then there was the period when they would send him jeans. American Levi’s were a big hit in Europe after the war. He could sell them easily on the street.

Somehow, during this time, he made his way from Bucharest, Romania to Dusseldorf, Germany. I don’t know how he did it. I just googled his journey. It’s 1,221 miles, the distance from San Francisco, California to Denver, Colorado. He had to travel through Hungary, Austria and halfway across Germany to reach Dusseldorf.

One time, when he was in Germany, in1955, Grandma sent him a copy of A Star of Hope, the poetry book Papa had written and dedicated to her for their 50th Wedding Anniversary. Maximillian wrote back. He was furious. Apparently the German censors, or someone in authority, thought it was some secret code and he was in serious trouble for a while.

Time went on. More packages were sent to Europe with things to sell. Then, at some point, Maximillian wrote to my grandparents and parents. He thanked them all for their help and let them know that they no longer needed to send him things to sell. He was fine. Life was good. He was working in a bank in Dusseldorf, Germany.

My parents and grandparents always believed, after they got that letter, that he had found a way to access Abram’s money. They were so close. He was his younger brother. It seemed only logical that Abram had told him the numbers of his Swiss bank account. We always believed that that was the money he lived on. The job in the German bank was helpful but the salary wouldn’t have been enough for the life he was living.

“Well, time marches on,” as my mother says. My parents and grandparents wrote and Maximillian wrote back. Many years passed. Grandma and Papa were no longer here. One day my Mom got a letter from Dusseldorf, Germany, from Fanny. Who was Fanny? She wrote to my Mom that she and Maximillian had married shortly after the war. Maximillian had just died. She wanted his family to know.

My parents were stunned. Maximillian had never mentioned a wife. They had no idea. To this day my Mom says, “Why? Why didn’t he tell us?” They would have been so happy to know he had somebody.

Mom and Fanny corresponded. It was complicated. My Mom would write a letter. Fanny would get it. She didn’t speak English. So she would take several buses to a friend’s house who did. The friend would translate Mom’s letter for her. Fanny would write an answer. The friend would then translate it into English and Fanny would mail the letter to Mom.

This would happen once a month for many years. Then one day Fannie wrote that she was very old. All the traveling by bus and transferring from one bus to another to get to her friend’s house so the letters could be translated was too much for her. She couldn’t do it any more. My Mom heard nothing more for a while. Then Fannie’s friend wrote that Fannie too had died.

In the end, Abram’s money did a lot of good. Knowing how generous he had always been in life with his family, I think he would have been happy with what his money accomplished after he was no longer here: It helped Maximillian and Fanny have a nice life and allowed Fannie to live comfortably all the years after Maximillian died.