Lists, rankings and ratings eliminate some of the guesswork in life. For example, instead of chancing a bad experience, I check rating websites for a restaurant, a movie or even a church. Goodreads and other online forums allow readers to post comments and ratings about novels or collections of stories. How would the general population rank Chekhov’s short stories? The half-dozen books on my desk about Chekhov or Chekhov’s anthologies are the old way of researching. I need guidance on where to begin, what is considered the best of Chekhov and how to do all of this in the quickest amount of time.

Lists, rankings and ratings eliminate some of the guesswork in life. For example, instead of chancing a bad experience, I check rating websites for a restaurant, a movie or even a church. Goodreads and other online forums allow readers to post comments and ratings about novels or collections of stories. How would the general population rank Chekhov’s short stories? The half-dozen books on my desk about Chekhov or Chekhov’s anthologies are the old way of researching. I need guidance on where to begin, what is considered the best of Chekhov and how to do all of this in the quickest amount of time.

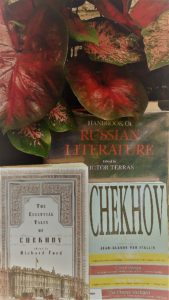

An Editor’s Choice

Books like The Essential Tales of Chekhov edited by Richard Ford offer a method for reading the best of Checkhov. Ford, a temporary Michigan transplant from the South, attended Michigan State University and writes in his introduction to the Chekhov anthology that Chekhov is a writer for adults. Chekhov’s most frequent themes of adultery, poverty and illness are not exactly the hero’s journey that Hollywood pumps into most movies. Chekhov’s plots pale and blur while his characters are noteworthy. My Russian dentist who inspired this literary trek says Chekhov descriptions, such as in “A Man with a Case,” have become Russian cultural references for describing personality types. After reading every Chekhov story, Richard Ford chose his favorites. He admits to adding a few stories that were not as polished and complete as Chekhov’s later works. In Ford’s opinion, “The Lady and the Dog” is one of Chekhov’s finest short stories.

Ranker.com

Since I read Ford’s number one pick, I wanted to compare other lists. ListVerse.com which compiles top ten lists of the bizarre to scientific failed in the literary realm with only three lists:

Top Ten Books of All Time (#9 The Stories of Anton Chekhov)

Top Ten Greatest Writers (#3 Pushkin with Russian runner ups of Tolstoy, Chekhov and Dostoyevsky)

Ten More Strange Moments In the History of the Novel Awards (no Russians until 1933)

My prize discovery is Ranker.com. This website allows viewers to vote for their favorites on people, entertainment, sports, culture and videos. Curious if the general public could be trusted to rank a literary giant like Chekhov, I find the ratings are generous for a guy who died in 1904. Here are the lists containing Anton Chekhov:

Best Anton Chekhov Short Stories

The Best Writers of All Time (#25 Chekhov)

Best Novelist of All time (#50 Chekhov)

Best Short Story Writers of All time (#3 Chekhov)

Dying Words Last Spoken by Famous People (#69 Chekhov)

The Greatest Playwrights in History (#2 Chekhov)

The Best Russian Authors (#3 Chekhov)

The Hottest Dead Writer (#3 Chekhov)

Every Person Who Has Been immortalized in a Google Doodle

I confess to spending more time on Ranker.com than in Chekhov’s actual writings. In regards to the primary mission of finding Chekhov’s best short stories, the survey says . . . the following stories received the most votes:

The Lady and the Dog (18 pages written 1889)

The Bet (9 pages written 1888)

Ward No. 6 (48 pages written 1892)

The Death of a Clerk (4 pages written 1883)

Misery (6 pages written 1886)

Fast Pass to Chekhov

If narrowing the reading to a handful of stories is still too much, then do what theme parks call the “fast pass.” Similar to a theme park’s shorter line, this method makes the classics very easy, fast and fun. I can listen to more stories than I have time to read.

The Duel (an independent film made in 2010 with an 81% on the Tomatometer)

“The Bet” (produced by ITV’s “The Short Story”)

The Seagull (a live performance by the Michigan Shakespeare Festival)

The Seagull (a 1975 production with a Rotten Tomatoes Audience Score of 50%)

Both professional and school productions of Chekhov’s stories are found on YouTube. Fans of silent movies will want to watch the short 2012 adaptation of Death of a Government Clerk by Ethan Unklesbay. Audio recordings are also on YouTube including the free online digital libraries of Librivox.org, read by volunteers. “Misery” is a good recording.

NPR produces Selected Shorts. The July 2017 program, hosted by Krista Tippett, begins with a Sherwood Anderson short story, continues to two poems by Tracy K. Smith and stories by David Whyte and Elizabeth Crane and finally ends with “An Enigmatic Nature” by Anton Chekhov. I veer off track to listen to Stephen King’s “Batman and Robin Have An Altercation.” This story is on Selected Shorts Too Hot For Radio. (I’m not counting this as a complete diversion because Stephen King’s Misery came to mind when I first saw the short story title of “Misery” by Chekhov.)

In conclusion, Chekhov’s short stories are for the reader to experience many times and in many ways. Ranker.com and Richard Ford helped begin my journey, but there are many stories remaining for me to enjoy. Each different story makes me fall a little bit more for the #3 Hottest Dead Writer.