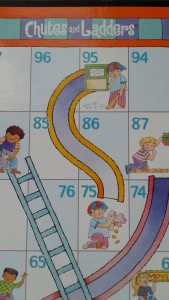

Games teach the mechanics of plot. A player begins Chutes and Ladders on a path with some ladders up and some chutes down. The sequence of action and consequence is plot, pure and simple.

Games teach the mechanics of plot. A player begins Chutes and Ladders on a path with some ladders up and some chutes down. The sequence of action and consequence is plot, pure and simple.

Same Game Different Century

The Milton Bradley game comes from an ancient Indian game called Snakes and Ladders. In Moksha Patam, the game follows Hindu philosophy and morality lessons with few ladders for virtues and many snakes for vices. Salman Rushdie wrote in Midnight’s Children about the game as “the eternal truth that for every ladder you hope to climb, a snake is waiting just around the corner, and for every snake a ladder will compensate.”

Mastering the Game

Snakes are consequences for vices such as disobedience, vanity, vulgarity, theft, lying, drunkenness, debt, murder rage, greed, pride and lust. These plot elements sound like the playbook for Netflix’s House of Cards. In the television series, plot twists are the norm, and consequences rarely weigh on the characters’ decision to act. Character development and flaw emerge as the driving force for plot (see Plotting for the Flaw). In House of Cards, each character’s manipulation, deception and corruption goes without consequence, until the proverbial house of cards tumbles to the ground.

The Parallel Plot Game

Beyond the character contributions to plot, the game board offers second attempts and alternate possibilities—both forms of parallel plots. For example, every child playing this game, has counted the spaces to the next ladder and hoped to roll that exact number. Often, the die indicates a number short of the goal, and the outcome of the game changes. When I missed a ladder, or even worse when I landed on the long slide back to the beginning, I thought what if . . . what if . . . I had rolled one space more.

The What If Game

The movie, Sliding Doors, is the one space more plot. The film shows two alternate realities based on either catching a train or missing it. Children’s books, such as Goosebumps by R. L. Stine, try this format with choosing different outcomes by flipping a coin, but the choice is one or the other. Sliding Doors shows both outcomes at the same time, jumping between each version in a confusing medley of scenes from the beginning of the film until the ending. As with other parallel plots, the emotional highs and lows are braided and mirrored with the two plot lines (see Paula Picked a Plighted Path . . .). With characters in common, the two plot lines—although parallel and in alternate realities—occasionally trip over each other in theme and traipse into the same settings at even the same times. While this film’s structure rates high for creativity, the challenge is how to bring two stories spiraling in different directions back together at the end. In this film, the solution is a similar event in the same setting with alternate outcomes—life or death. Another example of alternate realities is Maybe in Another Life by Taylor Jenkins Reid which shows alternating chapters of the protagonist’s choices.

The “Back to Square One” Game

In the “back to square one” scenario, a player is trapped and stuck in a repetitive loop of one ladder and one chute. What happens the second time around? The same events? Different? In the movie Groundhog Day, this different perspective occurs and reoccurs as a form of parallel plots. The protagonist tests the limits of his actions (vices) in a seemingly endless cycle of romantic comedy consequences of the “boy loses girl” variety. Eventually, the character decides to use his recycled groundhog days to improve his behavior (virtues), and the character arc takes him to the romantic comedy conclusion of “boy gets girl.”

The Next Generation’s Game

My basement is fertile ground for role playing games such as Grand Theft Auto. In GTA IV, the gamer chooses one of three characters, one of three parallel plots. Video games intensify the game playing experience of previous generations. Readers from this generation will expect parallel plots and creative structures beyond the basics of story.

Karen, well done! You pointed out the ultimate plot/lesson in life: our actions and decisions have consequences. Sometimes they result in something good and sometimes not. As Bob Barker used to say at the end of the TV show, _Truth or Consequences_, “Hoping all your consequences are happy ones.”

Kelly, you surprised me. I have never seen that game show – only Bob Barker in the Price is Right. How did this happen?

You provided a very interesting take on plotting. Thanks for the insight!

Thanks Sue. Hope you will share your comments on the “interesting takes” yet to come.

Karen, you’ve done a marvelous job of showing us that games teach the mechanics of plot. Interesting blog.

Thanks Barbara, teaching is your expertise. As I considered action and reaction, Chutes and Ladders seemed logical and whimsical. After some research, I discovered the fascinating history of this childhood game.

There are so many different games !

I enjoyed to read it.

Thanks Kook-Wha. I only scratched the surface of games. Do you like the subheadings?