The name, Leo Tolstoy, carries a bit of an intimidation factor. Tolstoy lived in the 1800s, and the world has changed since then. Many writers have come and gone, yet Tolstoy continues to be relevant.

At the library, I find several nondescript volumes lacking flashy colors, fonts and modern graphics. Recognizable titles include War and Peace (1400 pages), Anna Karenina (750 pages), The Cossacks (160 pages) and The Death of Ivan Ilyich (53 pages). I weigh my decision because quite literally my book bag is an unhealthy amount of heavy, and the winner is The Death of Ivan Ilyich. I load the three audio disks for my next commute to work and prepare for an easy week of listening to some old guy’s story about a different time and place. Instead, I discover “a dimension as vast as space and timeless as infinity . . . [that] lies between the pit of man’s fears and the summit of his knowledge.” It is an area called the Tolstoy Zone.1

At the library, I find several nondescript volumes lacking flashy colors, fonts and modern graphics. Recognizable titles include War and Peace (1400 pages), Anna Karenina (750 pages), The Cossacks (160 pages) and The Death of Ivan Ilyich (53 pages). I weigh my decision because quite literally my book bag is an unhealthy amount of heavy, and the winner is The Death of Ivan Ilyich. I load the three audio disks for my next commute to work and prepare for an easy week of listening to some old guy’s story about a different time and place. Instead, I discover “a dimension as vast as space and timeless as infinity . . . [that] lies between the pit of man’s fears and the summit of his knowledge.” It is an area called the Tolstoy Zone.1

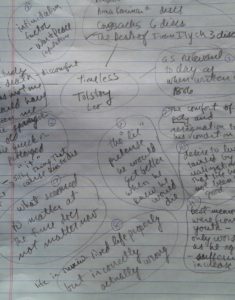

Within minutes of beginning this novella, I want nothing more than to continue. Often, I stop and marvel at Tolstoy’s timeless words and characters. I bubble the aspects of theme that intrigued me as shown in the photo.

The “D” Word

In this novel [spoiler alert] Ivan Ilyich dies. Death is part one of Tolstoy’s two-part story. The author approaches theme like a shark circling its prey. On each pass, the shark takes a closer look at what it will consume. The Death of Ivan Ilyich begins with the outside view of death. How do the living view the dead? By reading the Gazette, Pyotr Ivanovich sees the obituary placed by the widow, Praskovya Fyodorovna Golovin. The shocking news becomes an opportunity for career advance for some and a relief for others. Ivan has died and not me. The friend, Pyotr, is one of only two guests for the funeral. Uncomfortable realities exist in this time period when the dead remain in the home slowly decomposing for days; when an untimely and early death jeopardizes a family’s finances; and when illness causes long periods of declining health to a miserable end. Tolstoy leads the reader with Pyotr to the next revelation–fear. Next time, it might be me who dies.

Fear and death are universal themes much older than the 1880s. Biblical passages, such as John 11:38-44, have cultural ramifications of Lazarus’ death for Martha and Mary. Also, Ezekiel 37:1-14 symbolizes Israel’s hopelessness with a valley of dry bones. Death is both literal and figurative and represents aloneness, separation, desperation, destruction, loss of relationships and loss of possibilities. Tolstoy’s study of emotion is intimate, realistic and all encompassing. He writes of what modern readers recognize as the stages of grief published roughly a hundred years later by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross in her famous book On Death and Dying.

Life after Death

Ivan is dead, and Pyotr scuttles off to resume his card game and find a permanent replacement for his friend’s vacant seat. The circling shark has swallowed the prey. So what does Tolstoy do? He analyzes how the subject tastes from beginning to end and resets the clock to show how this terrible situation occurred.

The story changes narrators and pivots to be about life instead of death. If this sounds religious, it is no coincidence. According to Richard Pevear’s introduction for Tolstoy, The Death of Ivan Ilyich & Other Stories, Tolstoy began a personal religious conversion to moral teachings known as “Tolstoyism,” and eventually published What is Art? to receive worldwide recognition.

If I am to read like a writer, I know “what” happens in this story and “why” this novella wrestles with finding meaning in life. The beauty in the story is “how” this message unfolds through Ivan’s thoughts about his life. It feels like a geometric proof written as poetry. Each statement builds upon the next. The narrator wants to live, but, then again, no; he only now considers the lack of meaning and suffering in his life. Although he has tried to be proper and correct, he lived his life wrong and failed to help the people who needed him the most. The transformation of Ivan’s character with only internal monologue is the key to Tolstoy’s mastery. Very clearly, Tolstoy uses Ivan Ilyich as an example of what not to do. Of course, it is an alert to change, but the final message is comforting. If Ivan Ilyich can find peace, so too can everyone else.

Tolstoy is approachable in this timeless novel. All of my earlier fears were wrong. I may never tackle War and Peace, but I appreciate Tolstoy’s writing.

- Rod Serling, The Twilight Zone Series 1963.